Designing for Health Sciences Education: Pivoting to the Future of Healthcare

This is the second article in six-part Designing for Health Sciences Education series.

In the first article of this Designing for Health Sciences Education series, Understanding Today's Challenges, we looked at three of the major driving forces or themes behind designing for health sciences education today. These included the acceleration of digital learning, generational influences on students and faculty, and advances in understanding how we learn. In this article, we look at a fourth and final impact: the evolution of healthcare and medicine. We examine how some of the most significant healthcare innovations and disruptions from recent years have translated to health sciences curricula and what today’s health sciences students need to learn. We then consider what this means for the spaces that we design to support students and faculty in pivoting to the future of healthcare.

Drivers of Transformation in Healthcare Delivery

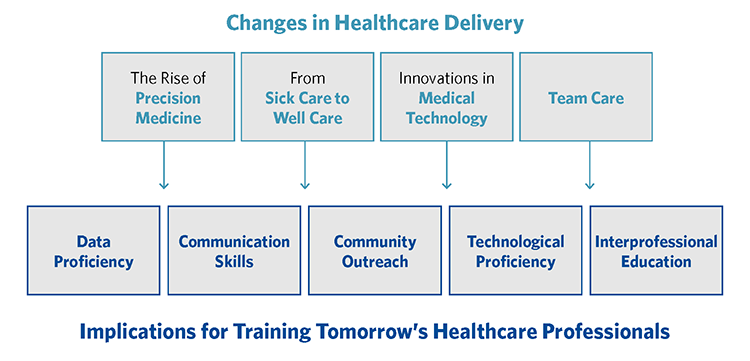

Over the last few decades, globalization, an aging population, the rise of chronic illnesses and changing demographics have reshaped how we think about healthcare. Healthcare solutions that reduce public health threats and prioritize wellness, address a growing number of eldercare and chronic disease management needs, and consider health disparities with a more targeted approach have become priorities. Meanwhile, advances in biomedical research have greatly expanded our view of what’s possible for treatment and prevention. Below are four of the major changes we have seen in U.S. healthcare delivery and how those are impacting health sciences education.

The Rise of Precision Medicine

Over the last three decades, precision medicine — the ability to target specific diseases based on genetic information and to predict how individuals will respond to various treatments — has revolutionized healthcare. As a result, the healthcare professionals of tomorrow need to be trained in:

- Data Proficiency: Healthcare professionals must be agile in accessing diagnostic data and matching that data to the specific symptoms and the health record of a patient. They will need to be able to monitor the success of these treatments in large data sets that then further informs and hones targeted care.

- Communication Skills: They also must be able to communicate effectively with patients and their families to help them understand the reasons for the recommended treatment so they will comply. Clear communication is crucial, since patients and families have access to medical information, both accurate and inaccurate, that might or might not apply to them.

From Sick Care to Well Care

Healthcare institutions are increasingly adopting a population health approach to care – embracing the idea that keeping individuals from contracting illnesses and medical issues is preferable to treating them after they are already ill or hurt. Community health education and localized, easier healthcare access allow individuals to avoid the emergency room and hospital for minor or chronic problems. As a result, the healthcare professionals of tomorrow need to be trained in:

- Community Outreach: The focus of nursing education, which has traditionally been on caring for very sick patients in the hospital, is broadening to include community practice in urgent care, home care, school nursing, pharmacy clinics, and medical office practices. Learning the tools, technologies and strategies for public and population health education are important aspects of medical and nursing education today. As students venture into the community to provide care, debrief spaces on campus will be needed for them to report their experiences and get feedback and additional insights into their experiences.

Innovations in Medical Technology

The healthcare industry is embracing new technology at a furious pace, including virtual care, health systems integration, infection control dashboards, predictive analytics, remote monitoring, mobile health care units, wearable technologies, and predictive fall prevention systems. These technologies are already in use and developing rapidly. As a result, the healthcare professionals of tomorrow need to be trained in:

- Technological Proficiency: Health sciences education is embracing this technology, equipping students to emerge from their education with an understanding of how the tools work and where they are best applied, as well as with the critical thinking skills to embrace and adopt new technologies as they continue to emerge.

Team Care

More emphasis is increasingly placed on the team in patient care, and the contributions of each member –nurse, doctor, specialty, pharmacist, et al. — are generally recognized in providing the best care. As a result, the healthcare professionals of tomorrow need to be trained in:

- Interprofessional Education: Today, greater emphasis is placed on interprofessional education and team-based learning, where multiple disciplines are trained together and given more opportunity to interact throughout the course of their studies.

Designers, planners and builders of learning environments must consider how best to design spaces and infrastructure to address these aspects of health sciences training. IT requirements for computational and data analytic needs should be considered. Simulation spaces that go beyond the operating table or the patient room should be incorporated. New and ever-changing technology must be factored into the budget from the outset. And spaces that were originally designed for learners of a single discipline should be rethought to accommodate different disciplines in a common exercise.

A Look at Nursing and Medical Education Today

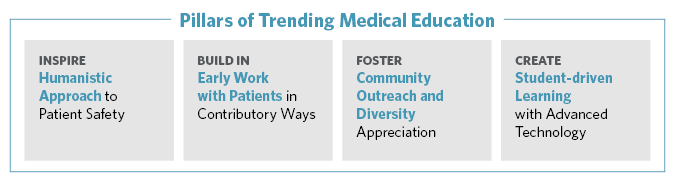

In response to the changes impacting healthcare, there has also been a significant shift in how educational institutions think about health sciences education.

Changes to Nursing Education

Increasingly, the American Association of Colleges of Nursing is encouraging a higher level of education for nurses. In 2015, they set goals that by 2020, the level of education for 80% of practicing nurses would be at the baccalaureate level and that the number of advanced degree nurses, master’s level and above, would double. In addition, nurses would ideally enter jobs where they could practice at the highest levels of their education. For example, nurse practitioners and other advanced nurses can practice as primary care providers. 1 This call for change has some wide-ranging effects on how nurses are educated. Requiring a BS in nursing at the entry level means more basic science and anatomy in nursing education. Doubling the number of advanced practice registered nurses means more master’s degrees, Ph.Ds. in nursing and doctors of nursing practice.

Like most branches of health sciences education, nursing students’ readiness for practice continues to move toward competency-based education. Traditional nursing competencies have included coordination and management of care, patient education, public health intervention and transitional care. However, bridging the gap between coverage and access as well as coordinating increasingly complex care are growing roles for nurses.2 Similarly, nursing students are being taught to develop critical thinking skills that allow them to use their role as the first and closest care provider for patients to evaluate the healthcare system for inefficiencies or ways that patient safety could be improved.

All of these developments translate to health sciences education institutions increasing the number of sections and courses in leadership, health systems science, and health policy.

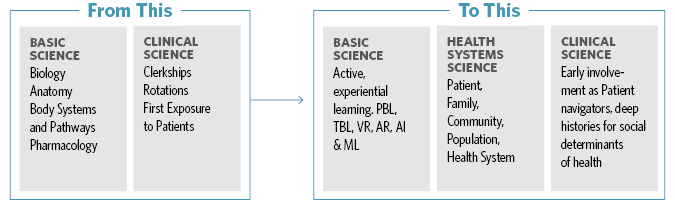

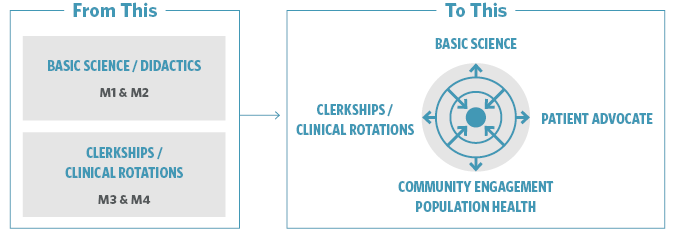

Changes to Medical Education

The education of medical students is undergoing transformation as well. Until the last decade, medical education had not changed very much since the early 1900s. Traditionally, medical school years 1 and 2 involved didactic/classroom learning, and years 3 and 4 involved a series of clinical rotations. This structure was based on the idea that students first needed a thorough background in basic science and anatomy before any interactions with patients. However, there is an initiative by some schools to move away from the current strict time requirements and mandated courses to competency-based education. In 2013, the American Medical Association began an initiative to stimulate innovation in the education of medical students, entitled “Accelerating Change in Medical Education,” which as of this writing has a total of 37 medical schools engaged in the effort to jumpstart curricular and process changes.3

There are six basic tenets of the “Accelerating Change” initiative:

- Developing flexible, competency-based pathways [to being a doctor]

- Teaching new content in health systems science

- Working with health care delivery systems in novel ways

- Making technology work for learning

- Envisioning the master adaptive learner

- Shaping tomorrow’s leaders

Today, in addition to basic science and clinical science, health systems science becomes the third leg of the educational stool. This new impetus in understanding the impacts of medicine and healthcare beyond the individual patient to both the health care system and the population has effects on healthcare practitioners that are both broad and deep.

Additionally, rather than a prescribed four-year timeframe with two years of basic science followed by two years of clinical rotations, today’s medical education may be quite different. Opportunities are often created for first and second year students to become involved with patients as advocates and active observers, volunteering and shadowing in clinics under supervision, taking medical histories, navigating today’s increasingly complicated health care systems, and following the same set of patients throughout their medical school careers.

In addition, ways to streamline medical education both in timeframe and cost are beginning to develop. A European model of medical education takes students straight out of secondary school, requires them to pass written and oral entrance exams in biology, chemistry, anatomy, physics, etc. (within 6 months to a year) and takes them through six years of regulated study. This model produces doctors six to seven years after secondary school as opposed to the eight year minimum required in the U.S. As the AMA and the LCME move toward a competency-based model, it will be interesting to see how accreditation of innovative programs in the U.S. and Canada may dovetail with this more streamlined model.

As schools are accredited and reaccredited, their efforts to provide a medical education will be geared toward producing doctors with the basic knowledge of biology, pharmacology and anatomy they need as well as knowledge of the wealth of medical technology, diagnostic tools and software available, medical ethics and communication skills to help their patients arrive at the best course of action, and the intellectual tools to engage in life-long learning.

Transforming the Health Sciences Learning Environment

The spatial impact of the current evolution within health sciences fields and education is profound.

Simulation and Clinical Skills Labs: Simulation and clinical skills centres play an increasingly significant role in providing active learning environments specific to allied health, nursing and medical students. Highly specific instrumentation for both diagnostics and care will need specialized spaces, designed both for efficient instrument performance and good visibility of the students learning to use it by their instructor.

Lecture Halls and Team-Based Classrooms: Large lectures may still have a place in health sciences education, but ideally in a flat-floor flexible room with movable furniture, rich technology and appropriate sightlines and acoustics to allow multiple pedagogies. Ideally, these lecture halls have adjacent breakout rooms for the large class to work in small groups with the concepts they have been given in lecture.

Support Spaces: As students venture earlier in their education to different clinical venues, they need spaces within their primary educational environment to discuss their experiences with each other and with faculty mentors, advisors and coaches. They will also need safe spaces to engage with those advisors and each other, and to relax and care for their own physical, mental and emotional well-being.

Greater elaboration on the evolution of learning environments for health sciences education with be the focus of upcoming articles within this series.

References

- American Association for College of Nursing, 2019, AACN's Vision for Academic Nursing White Paper.

- Washington, D.C. National Academies Press, 2011, The Future of Nursing: Leading Change, Advancing Health.

- “Accelerating Change in Medical Education.” American Medical Association, www.ama-assn.org/education/accelerating-change-medical-education.